Back when Assistant Professor of Informatics Stacy Branham was a still postdoc, her first research paper focused on how blind and sighted partners work together to make their homes mutually accessible. She had originally discussed both “independence” and “interdependence” in the home, but the section on interdependence did not make the final cut for 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. However, at that CHI 2015 conference, Branham concluded her paper presentation by saying that the challenge going forward would be to “design toward interdependence.”

For the next two years, Branham continued to discuss the topic. Then, in an August 2017 Facebook post, she asked friends with disabilities to weigh in on the “independence narrative,” which she compared to the “women can have it all” narrative of the women’s rights movement. Two colleagues responded: Cynthia Bennett, a Ph.D. student at the University of Washington, and Erin Brady, an assistant professor at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI).

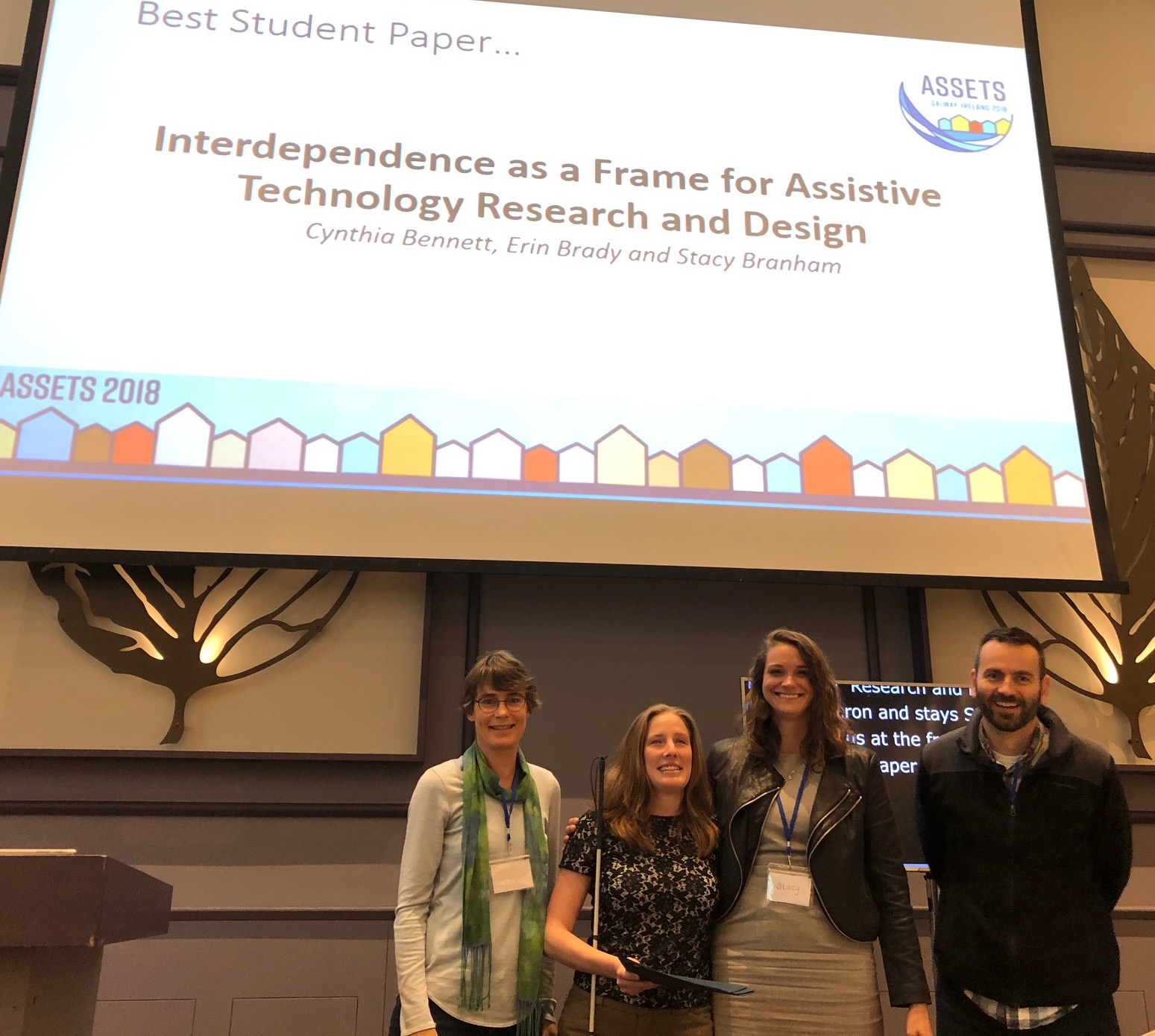

Fast forward to today, and the trio of researchers are co-authors of “Interdependence as a Frame for Assistive Technology Research and Design.” Their paper, which introduces “interdependence” to the ACM Special Interest Group on Accessible Computing (SIGACCESS), was not only accepted to the 20th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS 18) but also awarded Best Student Paper.

The award presentation: Program chairs Joanna McGrenere (far left) and David Flatla (far right), with Cynthia Bennett and Stacy Branham. (Photo credit: Matt Huenerfauth)

A Guiding Principle for Assistive Technology

“This paper has been four years in the making, from concept to actually turning it into a legitimate academic format,” says Branham, noting that the Facebook post was a turning point. “We pulled our conversation into a Facebook group chat, and the rest was history!” She explains that Bennett, an assistive technology researcher and a blind white cane user, “brought great depth of knowledge from the disability studies and disability activist communities,” complementing Branham and Brady’s knowledge of the assistive technology discipline and fields of computing and engineering.

“This research paper is the first official stake in the ground for the notion of ‘interdependence’ as a guiding principle within the assistive technology community,” says Branham.

She explains that a key goal of any assistive technology developed and studied in the SIGACCESS community is that it “enables a person with a disability to live a more independent life.” A variety of technologies have been developed to support this, including the NavCog system as well as BLAID, a collaboration between Toyota and a team led by Branham and Amy Hurst. The problem, says Branham, is that “research papers in my field rarely question what ‘independence’ means and why we care so much about it.”

From Independence to Interdependence

The ASSETS paper explores the history of the term “independence,” outlining how it derived from the Independent Living Movement — a civil rights movement originated by disabled activists that ultimately lead to legislation such as the American Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Rehabilitation Act. “It was important to talk about ‘independence’ at this time,” says Branham, “because many people with disabilities literally did not have any self-determination over their own lives.” However, what Branham and her co-authors point out in the paper is that independence doesn’t necessarily mean “done all by oneself.” Rather, it means “being treated like a full human being with self-determination.”

Furthermore, they found that modern disability studies scholars and disability rights activists — including scholars Ingunn Moser and Alison Kafer and activist Mia Mingus — have questioned using the term “independence” to motivate technology and policy design for people with disabilities. Instead, they prefer “interdependence.” Yet, according to Branham, “the assistive technology field has yet to pick up on this recent shift in language and philosophy.”

So the key achievement of the paper, explains Branham, is that “it translates the knowledge of feminist studies and disability studies to a predominantly engineering audience in the field of assistive technology.” It breaks down the concept of interdependence into four key tenets and demonstrates their applicability to assistive technology design, drawing on examples from field studies carried out in disability communities.

“There is no better feeling than to be able to share feminist, activist ideas with engineers such that they are not only understood but also recognized as relevant and significant to their digital practices,” says Branham. “This paper helps shift the narrative in ways that emphasize the humanity, the contributions and the collective interdependencies of all people — including people with disabilities — so that new technologies don’t unwittingly reproduce the same injustices of the past.”

— Shani Murray